Marketing Medicare Advantage to seniors of color – even when it’s bad for their health

By Matthew Cunningham-Cook

January 3, 2024

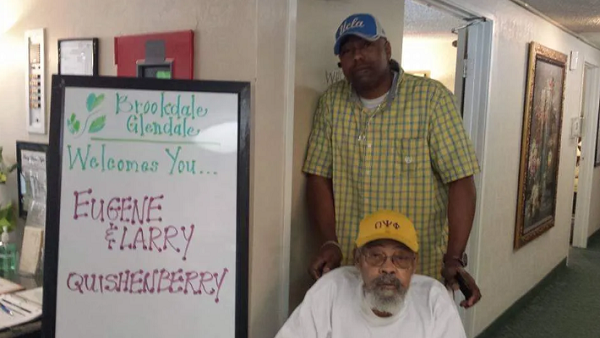

Eugene Quishenberry was 85 years old when his Medicare Advantage plan stopped covering his skilled nursing care. Less than a year later, in 2015, he died.

Eugene Quishenberry was 85 years old when his Medicare Advantage plan stopped covering his skilled nursing care. Less than a year later, in 2015, he died.

“It was weird. I came to visit him at the nursing home on Thanksgiving and they said, ‘Tomorrow we’re sending him home,’” his son, Larry Quishenberry, told HEALTH CARE un-covered.

“He hadn’t been able to do rehab at all because he was laid up in bed with these pressure sores on his feet,” Quishenberry said. He was sent home even though he got the pressure sores while he was in the facility. “They never took care of the situation that was created in their place and sent him home anyway. He basically spent that last year in bed,” his son said.

Larry Quishenberry sued his father’s Medicare Advantage plan, asserting that he was improperly denied benefits that he was guaranteed under state law. The plan was run by UnitedHealthcare, which has 29% of the overall Medicare Advantage market. The case made it to the California Supreme Court, where it was dismissed: The justices held that the denial of care was not actionable under state law.

Eugene Quishenberry was African American. In the United States, one in four older Black and Latino adults report that they faced racial discrimination in health care, disparities that appear to be particularly acute in Medicare Advantage plans, which are approved by Medicare but operated by private insurance companies. As opposed to traditional Medicare, which works with almost all doctors and hospitals in the country and rarely requires pre-approval before medical services are provided, Medicare Advantage plans typically exclude many providers from their “networks” and often insist that doctors and hospitals get “authorization” in advance, resulting in widespread care denials.

A 2023 report conducted by RAND Health Care and funded by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services found that “scores for Black Medicare Advantage enrollees were below the national average on 15 clinical care measures, similar to the national average on 19 measures, and above the national average on three measures,” with results even poorer for American Indian/Alaska Native populations.

Black and Latino seniors are more likely to be enrolled in a Medicare Advantage program than white seniors: 59% of Black seniors and 67% of Latino seniors are enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans, compared to 43% of white seniors.

A recent review of academic studies by KFF, a nonprofit health research organization, found that Black seniors in Medicare Advantage plans have been more exposed to preventable hospitalizations and readmissions, are not getting adequate access to mental health services, are less likely to see a specialist, and are more likely to be in a Medicare Advantage plan with lower star ratings.

A 2021 study by University of Pennsylvania and other researchers found that avoidable hospitalizations for Black seniors were more common in Medicare Advantage than in traditional Medicare, concluding: “Our findings provide evidence of racial disparities in access to high-quality primary care, especially in [Medicare Advantage].” The finding of avoidable hospitalizations buttressed a 2017 study finding that Black seniors in Medicare Advantage plans in New York state were twice as likely to be readmitted after major surgery as those in traditional Medicare.

Medicare Advantage plans have attracted scrutiny in recent months due to the reportedly frequent use of artificial intelligence to guide denials of care. Additionally, artificial intelligence in health care has been criticized for reinforcing racial disparities, with a 2019 study finding that an AI tool used by hospitals to predict care requirements understated the needs of Black patients. But as the KFF review notes, “Medicare Advantage insurers do not report data on prior authorization rates and denials by race or ethnicity, or the use of supplemental benefits for the overall Medicare Advantage population or by race or ethnicity.”

HEALTH CARE un-covered asked the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) if they planned to begin collecting data that shows denial rates by race and ethnicity. CMS indicated that they currently have no plans to require the collection of this data.

Dr. Claudia Fegan works at the public Cook County Health System, where more than 80% of the patients are Black and Latino, and where, she says, Medicare Advantage plans have been wreaking havoc on her and her colleagues’ ability to provide the care patients need.

[READ FULL ARTICLE HERE]