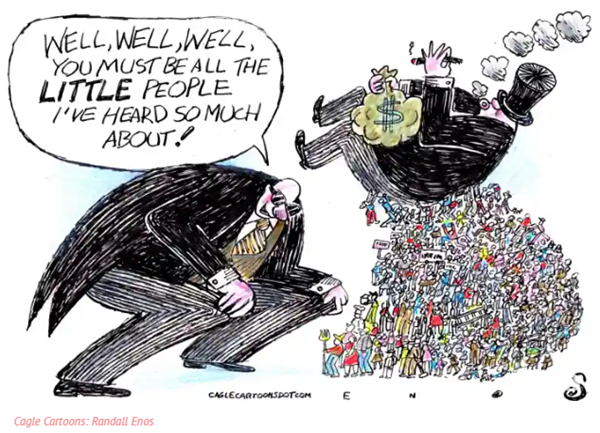

Should Seeking Profits Be Our Main Economic Priority?

By Walter G. Moss

September 20, 2024, 2024

Conservative capitalist economist Milton Friedman once wrote, “The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits.” Was he right? Let’s look at the case of Steward Health Care.

Conservative capitalist economist Milton Friedman once wrote, “The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits.” Was he right? Let’s look at the case of Steward Health Care.

Earlier this month (of September) the PBS News Hour featured a segment on it. In it host William Brangham interviewed The Boston Globe’s Mark Arsenault, who was part of the paper’s team that investigated the company’s 30 plus hospitals. Here is part of what Arsenault revealed.

“Steward Health Care was founded in Boston in 2010, when a private equity firm known as Cerberus Capital Management bought six hospitals.” Steward then bought up more properties and in 2016 made a deal with a “a real estate investment trust from Alabama.” According to the agreement, Steward sold much of the property on which the hospitals sat “and then leased them back, which generated a bunch of money for Steward, more than a billion dollars, most of which went to dividends, not into hospital reinvestment, but also straddled these community hospitals with significant rent lease payments.”

Arsenault went on to indicate that Steward failed its patients in two ways, shortages of staff—including nurses, doctors, and specialists—and “oftentimes routine equipment, supplies, maintenance on machines and even maintenance on buildings.” The shortages often meant that needed procedures were delayed. The investigative team found 15 cases where a person died because “Steward hospital that did not meet professionally accepted standards due to a lack of staff or a lack of supplies and equipment.”

One shortage case that Arsenault mentioned was that of a 31-years-old man whom the doctors indicated “needed one-on-one monitoring continuously.” But the Steward hospital, short of staff, could not provide it. “So when his heart stopped, there was nobody there. . . . to resuscitate him, nobody there to raise an alarm.” And he died.

While Steward suffered from shortages, its CEO did not. The Boston Globe reported that Ralph De la Torre often used the company’s jet and his own yacht for private pleasure trips in the Caribbean and Europe. “Passengers included . . . [his] fishing friends, a luxury yacht salesman, and high-profile horse trainers. . . . In many, if not all, instances, the private jet excursions were paid for by Steward . . . the funds pulled directly from the coffers of one of the nation’s largest . . . for-profit, private hospital chains.”

At about the same time as the above interview, a new book appeared by Thomas Piketty, who a decade ago had written the influential Capital in the Twenty-First Century. This French economist’s new book is entitled Nature, Culture and Inequality: A Comparative Historical Perspective. In an essay/interview about it, New York Times reporter Manuela Andreoni stated that “many countries, Piketty argues, were largely successful in expanding access to health care and education by taking these parts of the economy out of purely capitalist frameworks.

She then asked Piketty if he was suggesting that climate change should also “be taking out of the profit logic system because it’s a public good?” To which he responded, “Yes, exactly. At some point we have to replace market valuation by a sort of political valuation . . . to try to decide what’s valuable for us.”

Replacing the profit motive (or “market valuation”) by common-good considerations could apply to other areas besides climate, education, and health care, but instead we often see areas go in the opposite direction. Take, for example, for-profit prisons or an email I recently received (from Action Network) that began, “Louisiana, with its nine immigrant detention centers, eight of them run by for-profit corporations, has become a modern-day hell for migrants. These centers are designed to generate profit, not to provide care.”

Piketty’s response above suggests that Friedman was wrong when he wrote, “The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits.” Part of the social obligation of business is to recognize that to further the common good some areas have to witness (as Piketty pointed out) that profit and market valuation have to be replaced by political considerations. And the main purpose of politics—Pope Francis and many others have believed (see here and here)—is to further the common good.

For over a century, some critics of capitalism have recognized that the common good must come before profits. Take, for example, the U. S. Progressives of the 1890-1914 period. As one historian described it, their movement desired “to limit the socially destructive effects of morally unhindered capitalism, to extract from those [capitalist] markets the tasks they had demonstrably bungled, to counterbalance the markets’ atomizing social effects with a countercalculus of the public weal [well-being].” It wanted to constrain capitalism so that it served the common good.

A few decades later, President Franklin Roosevelt perceived himself as following in the tradition of earlier Progressives. And about three decades after FDR’s death, the British economist and environmentalist E. F. Schumacher (1911-1977) wrote, “Out of the large number of aspects which in real life have to be seen and judged together . . . [Western] economics supplies only one—whether a thing yields a money profit. . . . It does not even generally ask ‘whether an activity carried on by a group within society yields a profit to society as a whole.’” A half century before Piketty, Schumacher was also concerned about the…

[READ THE COMPLETE ARTICLE HERE]