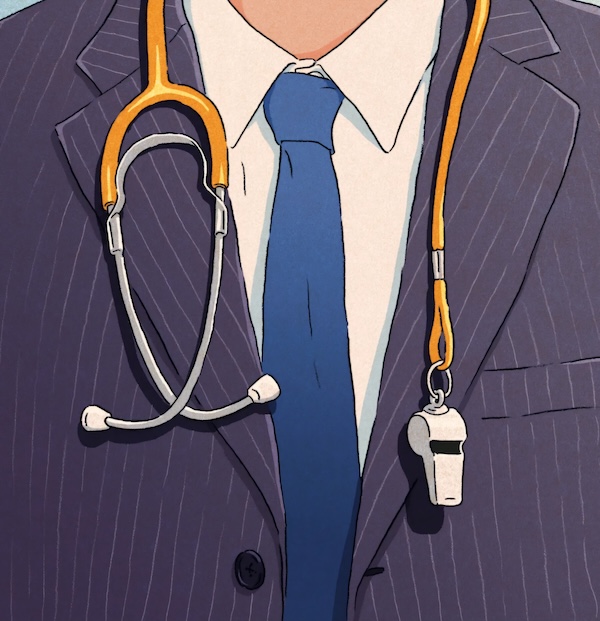

The Health-Care Executives Who Quit Over Greed

By Chris Stanton

March 28, 2025

After graduating from college in 1987, Ron Howrigon answered a help-wanted ad in the Sunday paper for a job at Kaiser Permanente, figuring a career in health care would make him a force for good in the world. Later, he made the leap to Cigna, where his specialty was negotiating payment rates with doctors and other providers, aiming to pay them as little as possible. In the early aughts, an order came down from his boss, Mark Bertolini, a major insurance-world figure who later became CEO of Aetna. According to Howrigon, Bertolini had decided Cigna was seen as too physician friendly, so Howrigon and his colleagues would need to drop 10 percent of the providers they contracted with from the insurer’s network. After some debate, they talked Bertolini down to one percent, and Howrigon cracked a dark joke: Why not cut costs by specifically targeting cardiologists and other vital but expensive specialists? He says Bertolini responded with a straight face and said he was onto something.

“I got this feeling in the pit of my stomach,” Howrigon says. “Like, My God, we’re going to terminate doctors out of network just to show ’em who’s boss, and we’re going to pick the doctors whose patients need them most.” According to Howrigon, Bertolini said they needed to “execute a few hostages.” He went through with it and kicked 150 doctors out of network without cause. (Bertolini, who now runs the insurance provider Oscar Health and has cast himself as an advocate for health-care reform and a progressive, yoga-doing figure in the industry, did not respond to a request for comment.)

It was clear to Howrigon that the profit motive meant the only way these insurance companies could satisfy shareholders was to “screw the people who need your product.” Hoping it would be different in the nonprofit sector, he took a job with a Blue Cross Blue Shield plan in Pennsylvania — only to find that it prioritized generating revenue as much as the for-profit plans did. Shortly after his employer cut payment rates to obstetricians, Howrigon’s wife had a successful C-section. Before he was even out of the operating room, his wife’s obstetrician told him, “Next time you take money out of a doctor’s pocket, remember today because I’m the one who was here.” That, Howrigon says, was his rock bottom.

He secretly used his paternity leave to devise an exit strategy. “I’d be much richer,” he says, if he had simply stayed put. “But it was making me into a person I didn’t like.” Howrigon now calls himself a “recovering managed-care executive” and works on the opposite side of the table, helping doctors negotiate higher reimbursement rates from insurers. In the process, he has run up against a hardball form of retribution from Cigna. After his business started having success in securing higher rates for doctors, Cigna gave some of his clients an ultimatum: Drop Howrigon or we’re kicking you out of network. In response, two clients said they would sooner terminate their contracts with Cigna than with Howrigon. The insurer backed off but still refuses to communicate with him directly. Now, when he negotiates contracts with Cigna, Howrigon says he has to play a “childish game” in which he emails messages to his clients, who then forward them to the insurance giant. “They won’t talk to me,” he says. “They’re holding a 20-year grudge that I left.” (Cigna did not respond to a request for comment.)

Even now, Howrigon says one of his friends, a medical director at a big insurer, won’t be seen with him in public. “What’s that old saying?”…

[READ THE COMPLETE ARTICLE HERE]