The Illusion of Choice

By Suzanne Gordon

August 4, 2025

At his confirmation hearing in January of 2025, Secretary of Veterans Affairs Doug Collins, a former congressman from Georgia, assured the Senate Veterans’ Affairs Committee of his commitment to provide specialized, high-quality medical care for the roughly nine million veterans enrolled in the nation’s largest and only truly integrated public health care system, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA).

At his confirmation hearing in January of 2025, Secretary of Veterans Affairs Doug Collins, a former congressman from Georgia, assured the Senate Veterans’ Affairs Committee of his commitment to provide specialized, high-quality medical care for the roughly nine million veterans enrolled in the nation’s largest and only truly integrated public health care system, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA).

But Collins, a chaplain in the Air Force Reserve, also explained that his mandate from President Trump is to make it “easier for veterans to get their health care when and where it’s most convenient for them,” by giving them greater choice between in-house and outsourced care. To do this, he planned to lean on the network of 1.7 million private-sector providers who are part of the Veterans Community Care Program (VCCP), created by the VA MISSION Act of 2018. Annual reimbursement of these non-VHA doctors, therapists, hospitals, and clinics now costs the federal government more than $30 billion per year, nearly one-third of the VA’s entire direct care budget.

Collins’s proposed budget for fiscal year 2026 calls for a 50 percent increase in discretionary VHA spending on private care and a 17 percent reduction in discretionary direct care funding. (The overall proposed budget for VA medical services increases, but only because of a large boost in the mandatory Toxic Exposures Fund, which provides health services for veterans exposed to burn pits and environmental exposures. All other diagnoses not in the TEF authorizing legislation would fall under the reduced discretionary budget, and even adding mandatory spending, private care is poised to increase at nearly twice the rate of VA direct care.) And Collins has taken other steps consistent with the goal of downsizing direct service provision and boosting the VHA’s reliance on outside vendors.

Republicans in Congress routinely assert that veterans can easily find better and faster treatment outside the VHA. That’s because they assume that we have enough hospitals, primary care providers, specialty physicians, and mental health therapists to care for the country’s current patient load of 330 million nonveteran Americans, let alone nine million more veterans.

To test the accuracy of these claims, the Veterans Healthcare Policy Institute (VHPI) partnered with the Prospect on a survey of the U.S. health care landscape in all 50 states. State by state, we looked at the data on the current available supply of primary care providers, mental health professionals, and hospitals, particularly in the rural (and remote rural) areas where about one-quarter of all veterans, or about 4.7 million, reside, with 2.8 million of them enrolled in the VHA.

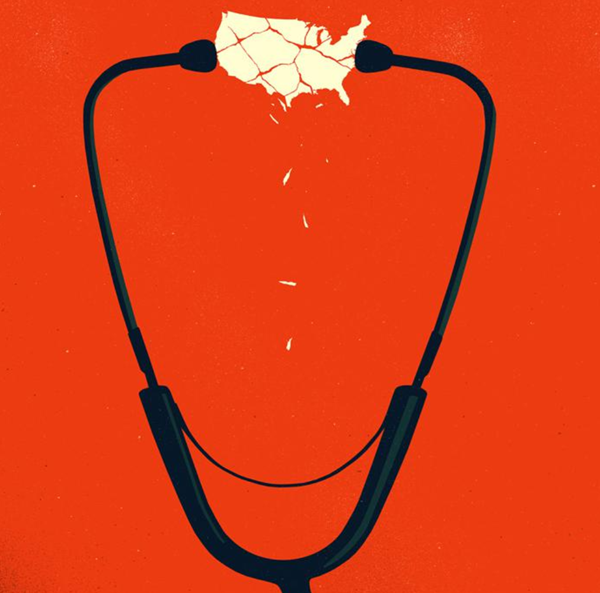

This analysis reveals a system that cannot provide even basic medical and mental health services to nonveteran patients. Hundreds of hospitals in America’s rural counties and underserved areas have curtailed critical services or closed entirely. And thousands of counties across America are experiencing significant health provider shortages, according to federal data.

VA patients receive a full spectrum of coordinated care to deal with the unique needs of those who served in combat.

The dramatic shortfall in capacity in our nation’s health system will get even worse with the passage of President Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill Act. On top of unilaterally imposed cuts that are already crippling the nation’s academic medical centers, the law, signed on July 4, will impose over a trillion dollars of cuts to Medicaid and the Affordable Care Act. Around 17 million people are expected to lose their health insurance due to Trump’s policies, guaranteeing increased uncompensated care at emergency rooms. States will also have less money to fund their Medicaid programs. All of this will lead to additional hospital closures and more shortages of health care personnel.

Yet, at precisely this moment, President Trump, VA Secretary Collins, and Republicans in Congress also want to send more veteran patients into an already troubled private-sector system, while depleting that system of the resources necessary to absorb this extra load. The idea that this will work well is shaped more by ideology than reality.

One longtime VA expert observed: “Imagining that you can add more complex VA patients into a private-sector system that will be reeling from, and contracting because of, funding cuts is nothing short of delusional.”

A Case Study in Coordinated Care

“Will Smith,” whom I have given a pseudonym for reasons of medical privacy, is a 75-year-old Army vet who fought in the Vietnam War. Because of his combat exposure, Smith struggled with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after leaving the military. Thanks to VHA therapists and many years of peer group support, he no longer abuses alcohol or prescription drugs.

Like other Vietnam vets exposed to Agent Orange, he has diabetes, which has led to chronic heart problems and kidney disease. Because of the heavy backpacks he carried “in country,” he also suffers from osteoarthritis in his hips and knees, severely limiting his mobility. To get around, he depends on an electric wheelchair provided by the VA. He takes 18 different drugs (all delivered free of charge) to help control multiple “co-morbidities.”

Smith’s primary care physician (who chose to remain anonymous, because in the current environment, saying anything good about a system the doctor’s bosses want to close could get the doctor fired) is responsible for coordinating with numerous specialty providers at the large VA medical center where Smith gets his care. The PCP consults regularly with Smith’s cardiologist, pulmonologist, nephrologist, and everyone else dealing with his physical and mental health problems, which have included suicidal ideation.

Smith’s Patient Aligned Care Team includes a medical resident who is training at the VA, like tens of thousands around the country. An RN, a licensed vocational nurse, and a medical service assistant—all of whom have known Smith for years—help make sure that he schedules and shows up for his appointments. A clinical pharmacist monitors Smith’s use of medications to ensure that he’s taking his pills correctly: some with food, some in the morning and not at night.

More than 89 percent of counties in the United States are officially designated Health Professional Shortage Areas.

Smith’s doctor schedules 60-minute, in-person visits with Smith every three months and a telehealth appointment every six weeks. In between these consultations, Smith’s weight and blood pressure are checked daily through a VA telemonitoring service, which sends alerts to his care team if worrisome changes are detected. There is no patient fee for this service. If Smith needs equipment essential to facilitate his care, like a laptop, iPad, or smartphone, the VA also provides it, free of charge.

The VA’s integrated health service provides Smith with acupuncture and chiropractic sessions to help him manage chronic pain. When able, Smith tries to attend a chair yoga class, one of many such offerings that include popular mindfulness meditation sessions.

Our pseudonymous Will Smith is not an outlier, in terms of his complex care needs. As a 2016 RAND report confirmed, “VA providers are likely to be treating a sicker population with more chronic conditions, such as cancer, diabetes, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), than the population expected by civilian providers.”

A 2021 report from Brown University’s Cost of War Project underscored that the open-ended global war on terror has produced …

[READ THE COMPLETE ARTICLE HERE]