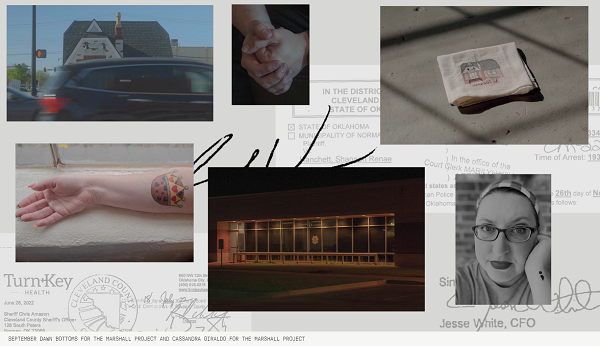

This Company Promised to Improve Health Care in Jails. Dozens of Its Patients Have Died.

By Cary Aspinwall, Brianna Bailey and Sachi Mcclendon

July 30, 2024

NORMAN, Oklahoma — Two days after Thanksgiving in 2022, Shannon Hanchett walked into an AT&T store for a new phone, and ended up in handcuffs.

Hanchett ran the Cookie Cottage, a popular bakery in this college town, where she made treats named for places across the state, from Stilwell Strawberry to Lawton Lemon. But lately, her mental health seemed to be fraying. She was falling behind on orders. Her marriage was crumbling. And the 38-year-old mother of two had picked fights with family and friends.This article was published in partnership with The Frontier.

It all detonated that day in the AT&T store. Employees phoned police after Hanchett began pacing, ranting and calling 911. Body camera footage shows an officer from the Norman Police Department talking to her for several minutes, then tackling, handcuffing and arresting her for misusing the emergency line.

Like so many people experiencing mental health crises in the U.S., Hanchett landed not in a psychiatric hospital, but in a county jail. In her case, it was Norman’s Cleveland County Detention Center, which contracts with a for-profit company to provide medical care: Turn Key Health Clinics.

And for Hanchett, that’s where things got even worse.

As local jails have morphed into some of the largest mental health treatment facilities in the U.S., many counties have outsourced medical care to private companies that promise to contain rising costs. Turn Key is one of the fastest growing in the middle of the country.

At least 50 people who were under Turn Key’s care died during the past decade, an investigation by The Marshall Project and The Frontier found. Our reporting unearthed company policies and practices that have endangered people in jail — especially those with mental illness.

In dozens of cases, Turn Key employees didn’t send people to the hospital when they were in crisis, catatonic or refusing to eat or drink. The company staffed mental health and other medical positions with low-level nursing assistants trained to perform basic tasks like taking vital signs, but not to diagnose or assess medical conditions.

Medical doctors and more advanced-level nurses working for Turn Key frequently consulted over the phone for a limited number of hours per week instead of making in-person visits, according to government records and documents obtained through lawsuits.

Until last year, the company often restricted the kinds of medicines it would provide people in jail, not giving them long-acting psychiatric drugs and prescriptions they had received before their arrests.

We obtained records from sheriffs who raised concerns about the company not providing the proper medications for people in jail with mental illness. “I have been told that Turn Key does not prescribe those types of medications,” one Texas sheriff wrote in a 2022 email. “This is causing a cascade of problems not only for their safety and well-being, but for the staff and facility as well.

Turn Key officials declined interview requests for this story. In response to written questions, the company issued a statement from its medical director, Dr. William Cooper: “Turn Key’s goal is to provide the highest level of care pursuant to the client’s budget. … The company continues to expand because of the quality of the care provided.” He added that Turn Key is “constantly working to build on the quality of care it provides.

To examine the company’s practices, we obtained records, including internal documents and emails between company leaders and public officials, in nearly 70 counties across Oklahoma, Texas, Arkansas, Louisiana, Colorado, Kansas and Montana. We also reviewed more than 100 lawsuits involving jail deaths and injuries. Many were dismissed for not meeting legal hurdles required for civil rights lawsuits: Plaintiffs must prove that the company wasn’t just negligent, but showed “deliberate indifference” to patients’ medical needs, among other requirements. Some suits resulted in settlements, many of which were confidential, and nearly two dozen suits remain pending.

A woman in Colorado died after …

[READ THE COMPLETE ARTICLE HERE]