“Unconscionable”: American Pediatrician Who Worked in Gaza Hospital Recalls Horrors of Israel’s War

Interview with Dr. Seema Jilani by Democracy Now!

February 6, 2024

Democracy Now! speaks with Dr. Seema Jilani, a pediatrician who spent two weeks in Central Gaza volunteering in the Al-Aqsa Hospital emergency room. “I saw the fall of a hospital before my very own eyes,” says Jilani, who shares recorded voice notes from her time in the besieged territory while trying to save children in a health system collapsing under Israeli pressure and bombing. “I have never treated this many war-wounded children in my career.” Finally, Jilani shares why she continues to serve as a doctor in war zones with the International Rescue Committee. “It is the absolute honor of my life to serve the people of Gaza,” she says. “It is all of our responsibility to consider those orphans, consider those families who are completely bereft of any and all human dignity that has been taken from them. … Their fate will sit with us.”

Democracy Now! speaks with Dr. Seema Jilani, a pediatrician who spent two weeks in Central Gaza volunteering in the Al-Aqsa Hospital emergency room. “I saw the fall of a hospital before my very own eyes,” says Jilani, who shares recorded voice notes from her time in the besieged territory while trying to save children in a health system collapsing under Israeli pressure and bombing. “I have never treated this many war-wounded children in my career.” Finally, Jilani shares why she continues to serve as a doctor in war zones with the International Rescue Committee. “It is the absolute honor of my life to serve the people of Gaza,” she says. “It is all of our responsibility to consider those orphans, consider those families who are completely bereft of any and all human dignity that has been taken from them. … Their fate will sit with us.”

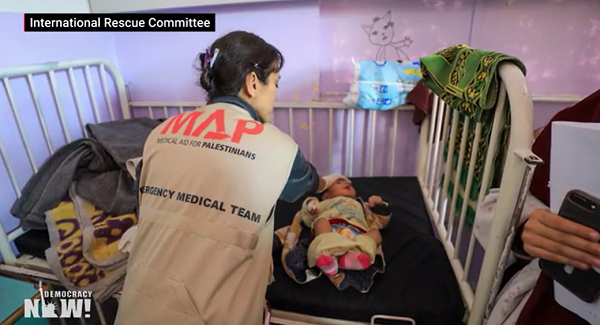

NERMEEN SHAIKH: We spend the rest of the hour with an American doctor who just spent two weeks in central Gaza. Dr. Seema Jilani is a pediatrician who volunteered in the Al-Aqsa Hospital emergency room as part of a team of doctors with the International Rescue Committee, where she’s senior technical adviser and leads their emergency health responses globally. The team included doctors from both IRC and Medical Aid for Palestinians.

Before she joins us, we’ll play some of Dr. Jilani’s voice notes that she recorded in Al-Aqsa Hospital’s emergency room and also at night in the compound housing the emergency medical team.

DR. SEEMA JILANI: We’re in the resuscitation room in Al-Aqsa Hospital. It’s a mass casualty, where the site of the mass casualty was a school. Of the five casualties, four are children. So, he was injured in the first day of the war.

UNIDENTIED: Yeah.

DR. SEEMA JILANI: And now we’re day 82.

UNIDENTIED: Yeah.

DR. SEEMA JILANI: And he’s waiting.

UNIDENTIED: Yeah.

DR. SEEMA JILANI: I’m so sorry.

I can hear the — I can hear the airstrikes coming in now. It’s about 2 a.m. And this is the sound of drones right outside my window, and also overhead flying more airplanes, I believe. I can’t sleep, so I decided to do this voice note. It’s a very specific hellscape that exists here in Gaza when you’re cursed enough to hear the words from a doctor that say, “Whose body part is that? Don’t carry it through the halls. I don’t want children seeing that.” And that is a quote from one of my colleagues in the emergency room, where we saw a leg being carried, a lower leg with the boot still on, sock still on. And it was being carried through the emergency room.

We have arrived here at Al-Aqsa Hospital emergency room. And what I’m seeing here is children lying on the ground, a double amputation on one child. And there are no beds available, so people are literally just on the ground seeking treatment. We’ve already had three parents come up to us and ask — they see the stethoscope, and they ask me, “Can you come see my child? Can you come see my child?” And I’m waiting for the local doctors to come in to be able to guide us through what we need to do and do a handover. There is one child that I’m looking at, approximately 8 years old, at the — lying on the ground. Next to him is a woman in a wheelchair who’s waiting to be seen. The one on the ground has bandages on bilateral lower extremities going all the way up, and looks like he’s been brought in overnight.

And we’re hearing right now that it was a terrible, terrible night because of the bombing in al-Maghazi, where people had been told to evacuate and then, subsequently, were bombed. There are definitely more people here than yesterday, and yesterday was very full. So, no beds available. As I said, people — there’s not really room or space for us to breathe or think. There’s a gentleman here that’s sobbing in front of me and being comforted by maybe his son, maybe a stranger. I don’t know. But he’s an older gentleman with a bandage on his head, and he’s just sitting and holding his head in his hands, crying and head hung low. And then there’s one, two, three, four, six children in my line of sight right now in the corner that need medical attention urgently, one of whom is crying, a little boy around 6 or 7 years old, wiping his tears. I can’t see the injuries clearly, but we’ll get started to work today to see how we can support and help them through this — through their tragedy.

UNIDENTIED: Rockets. They’re rockets. And they’re nearer than they were before.

DR. SEEMA JILANI: That feels very close.

UNIDENTIED: Because you don’t get to hear — you don’t get to hear much whistle before it comes.

DR. SEEMA JILANI: One morning, we arrived to a nurse who was quietly sobbing in the corner. His colleague had been killed the night before, and he had tried to resuscitate him in the emergency room. He is dignified in his grief. I asked, “Should we leave?” But instead, he just thanks us for our presence and asks us to see a few patients on his behalf. He just could not face the grueling work and the patients outside the room right now. I felt rewarded if I could be helpful to this one person in this one moment. As I was rounding about two hours later, I raised my head from a patient to see him, again, right back at work, as if nothing had happened.

The next day, we see a 23-year-old patient with his lower leg blown off so badly, it’s disconnected from its upper leg, floppy. I look down to plant my stethoscope on his chest, only to find him still wearing his UNRWA, or U-N-R-W-A, vest as a staff member. The only comfort I can provide him is to wipe the dried blood off his face, to moisten his dry lips as he yearns for some water, quietly lifting his neck for a little more. I quieten his fear with a wet washcloth to his forehead and some whispers of sweetness, of calm. None of these interventions are morphine. He died on the floor of a Gaza emergency room with little more than my hand in his hand and a washcloth to his forehead.

[READ FULL ARTICLE HERE]